“Readiness is the name of the game and the ability

of our people to respond is the second part of it.”

– Admiral Robert Natter, commander of the U.S.

Navy’s Atlantic Fleet on September 11, 2001 [1]

Navy personnel at the Pentagon on the morning of September 11, 2001, including some key officials, appear to have acted with a surprising lack of urgency after they learned of the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center.

Even though the Navy–along with the rest of the United States military–was responsible for protecting America if it was under attack, its personnel at the Pentagon seem to have done nothing, or very little, to help defend the country after they learned of the plane crashes at the World Trade Center. Remarkably, many of them continued with their normal work duties as if nothing unusual had happened. Furthermore, the Navy’s top officials appear to have issued no orders to their personnel, regarding what to do in response to the crashes.

The failure of Navy staffers at the Pentagon to promptly initiate a military response to the attacks is particularly significant because, among other things, the Navy had assets–including fighter jets–that could help defend the Northeast U.S. A quick response was critical so these assets could be deployed as soon as possible.

Navy personnel should also have responded immediately when they learned what had happened at the World Trade Center because their department would have been responsible for helping the rescue efforts in New York. The Navy was supposed to coordinate with the Army and the Air Force “on proposed action to support civilian authorities during emergencies involving mass casualties,” according to the Department of Defense’s book about the Pentagon attack. [2]

What is more, even before 9/11, the Pentagon was considered a likely target for terrorists. And yet, on September 11, Navy personnel–many of whose offices were damaged or destroyed when the Pentagon was hit–received no orders to evacuate and made no attempts to get out of the building of their own accord before it was attacked. And, apparently, no attempts were made to move the most senior Navy officials away to safer locations prior to the attack on the Pentagon. [3]

Unfortunately, the failure to take effective action quickly enough to prevent the attack on the Pentagon had serious consequences for the Navy. Percentage-wise, it lost more of its spaces at the Pentagon than any other military department did on September 11. [4] And a third of the 125 Pentagon employees who died when their building was hit worked for the Navy. [5]

In this article, I examine the actions of several senior Navy officials who were at the Pentagon on September 11. These include Admiral Vern Clark, the chief of naval operations; Vice Admiral Timothy Keating, deputy chief of naval operations for plans, policy, and operations; and Susan Livingstone, under secretary of the Navy. These officials all appear to have failed to respond appropriately after they learned of the crashes in New York.

I look at the goings-on in several key spaces in the Pentagon, such as the Navy Command Center and the office of the vice chief of naval operations. Like the senior officials whose actions I examine, personnel in these spaces appear to have responded to the crashes at the World Trade Center in a way that is far from what we might reasonably have expected.

I also look at a possible reason for the inaction of Navy personnel at the Pentagon. Specifically, I consider whether the Navy was involved in a training exercise on September 11 and this led to its staffers mistakenly thinking the crashes at the World Trade Center were simulated, rather than genuine attacks. If this was the case, it would indicate that rogue individuals in the U.S. military were involved in planning and perpetrating the 9/11 attacks, and deliberately created confusion that caused the Navy to respond so inadequately to the attacks.

CHIEF OF NAVAL OPERATIONS CONTINUED A BUDGET MEETING INSTEAD OF RESPONDING TO THE CRASHES

On September 11, Admiral Vern Clark, chief of naval operations, was in a meeting in his office on the fourth floor of the Pentagon’s E ring, discussing budget issues, when the attacks on the World Trade Center occurred. [6] (The Pentagon is a five-story building–which also has two basements–consisting of five concentric rings of offices. These rings are labeled alphabetically from A to E, with the A ring being the innermost ring and the E ring the outer ring. Clark’s office was therefore in the outer ring of the Pentagon.)

Vice Admiral Mike Mullen, deputy chief of naval operations for resources, requirements, and assessments, was with Clark in the meeting. [7] Admiral William Fallon, vice chief of naval operations, appears to have been there too. [8]

Although Clark had a television in his office that would have shown what had happened at the World Trade Center as soon as the coverage of the first plane crash–which occurred at 8:46 a.m.–began, that day the television was off. All the same, members of his staff reportedly “kept him informed of events at the World Trade Center.” Clark has commented that he also “knew that my Command Center … would keep me apprised of what was going on there.”

He has recalled that, after he learned of the second crash at the World Trade Center, which took place at 9:03 a.m., he “knew now that we had in fact witnessed an unprecedented act of terrorism.” And yet he appears to have done almost nothing in response to the attacks in New York. [9]

Clark said, on one occasion, that in the minutes just after he learned of the second crash, he “got up from this meeting, went over to my red phone, made a few telephone calls, talked to leaders in a couple of places.” [10] According to Mullen, a few minutes before the Pentagon was hit, Clark phoned Army General Henry Shelton, then-chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, “to query what we were doing,” since “it appeared that we were under attack.” Shelton replied that he had been notified that a plane was heading toward Washington, DC. [11]

Clark, however, appears to have done nothing to help initiate a military response to the attacks. He said, on one occasion, that after he learned of the second crash, he simply continued his meeting about budget issues. He said: “I’m embarrassed to say I didn’t even think about [the terrorists] coming to get us at the Pentagon. I had at other times. But at that moment I was focused on what was going on in New York. So we went back to work, and a few minutes later we heard this incredible explosion … and the Pentagon was hit.” And Sea Power magazine reported that Clark was still receiving his budget briefing when the Pentagon was attacked.

Furthermore, even though Clark, as chief of naval operations, was the most senior uniformed officer in the Navy, his staffers only came to evacuate him from his office after 9:37 a.m., when the Pentagon was hit. [12] And yet surely they should have wanted to get such a key official moved away to somewhere safer when it became obvious the U.S. was under attack–i.e. immediately after the second World Trade Center tower was hit–if not before then. Since Clark’s office was on the Pentagon’s fourth floor and in its outer ring, they should have realized that Clark was in an area of the building that would be particularly vulnerable–as compared to, say, a room in the basement–if the terrorists planned to attack the Pentagon.

DEPUTY CHIEF OF NAVAL OPERATIONS WENT AHEAD WITH AN UNIMPORTANT MEETING AFTER LEARNING OF THE CRASHES

Another key official who was at the Pentagon when the attacks on the World Trade Center took place was Vice Admiral Timothy Keating, deputy chief of naval operations for plans, policy, and operations. [13]

Keating learned of the first crash during the “operations update”–his daily intelligence briefing, held in the Navy Command Center on the first floor of the Pentagon. “We couldn’t understand how a pilot could make such a significant navigational error on a day when the skies were crystal clear blue,” he has recalled. But although they were “perplexed,” Keating and those with him “just kept going” with the briefing.

When the briefing ended, Keating went to his office, on the fourth floor of the Pentagon, and saw the second crash on television. Keating has claimed that, even then, he didn’t realize a major terrorist attack was underway. “It still didn’t occur to us what was happening, that this was a large-scale attack with catastrophic consequences,” he commented. [14]

In his office, Keating met with Edmund James Hull, the ambassador-designate to Yemen. Their previously scheduled meeting appears to have started shortly after 9:00 a.m.: Hull said it began about 30 minutes before the Pentagon was attacked, which would have been sometime around 9:07 a.m. The two men apparently ignored the fact that the U.S. was under attack. “We went ahead with the meeting nevertheless,” Hull recalled. [15]

The main topic of their discussion, according to Sea Power, was “the first anniversary of the terrorist attack on the guided-missile destroyer USS Cole on 12 October 2000 during a port visit to Aden, Yemen,” which had been “masterminded by Osama bin Laden’s terrorist network” and caused the deaths of 17 American sailors. [16] Hull recalled: “We briefly noted the events of New York but then proceeded to discuss future collaboration in Yemen. … I stressed my commitment to successfully completing the investigation of the Cole attack and bringing its perpetrators to justice.” [17]

Keating and Hull were still discussing the anniversary of the attack on the USS Cole when the Pentagon was hit, almost 35 minutes after the second attack in New York occurred. “We were discussing the fact that the Cole attack was coming up on a year’s anniversary–those were almost our exact words at the moment the plane impacted,” Keating recalled. [18] Just before the Pentagon was hit, Hull has written, “[W]e reviewed the situation [in Yemen] and our upcoming responsibilities.” [19]

Keating’s lack of action in response to the attacks on the World Trade Center seems particularly odd considering that, according to Sea Power, one of Keating’s responsibilities was to oversee day-to-day operations in the Navy Command Center. [20] The Command Center was responsible, among other things, for monitoring significant international events and keeping senior Navy officials informed of important developments. [21] In a situation like what occurred on September 11, then, it was surely more important for Keating to follow what was going on in this critical hub than discuss the anniversary of the attack on the USS Cole with Hull.

Hull’s inaction in response to the crashes also seems particularly odd since, in the two years before 9/11, Hull had been the principal deputy coordinator for counterterrorism at the State Department and had represented the State Department on Richard Clarke’s Counterterrorism Security Group. [22] He should therefore have been an expert on terrorism and have had a better understanding than most of the seriousness of the situation on September 11. Indeed, Hull has said that after he learned of the second crash, he had “the thought in mind that al-Qaeda had definitely undertaken a new operation in the U.S.” [23] And yet he proceeded with his unnecessary meeting with Keating as if nothing unusual had happened.

Furthermore, according to Shipmate magazine, even though Keating and Hull had “witnessed the devastating news of the attacks in New York,” they “didn’t question their own security” at the Pentagon. [24] They consequently made no attempt to get out of the building, despite it being a likely target for terrorists.

Keating has estimated that his office was “about 150 feet” from where the Pentagon was hit at 9:37 a.m. But his staffers only came and advised him and Hull to get out of the Pentagon shortly after the attack there took place. [25]

UNDER SECRETARY OF THE NAVY WENT AHEAD WITH A BRIEFING FOR A GROUP OF VISITORS AFTER LEARNING OF THE ATTACKS

A further important official whose actions at the time of the 9/11 attacks deserve scrutiny is Susan Livingstone. As under secretary of the Navy, Livingstone was the second-highest-ranking civilian in the Navy. On the morning of September 11, she was scheduled to hold a briefing for a group of 30 civilian employees of the Naval Surface Warfare Center (NSWC) in Crane, Indiana.

The NSWC employees were in Washington, DC, to complete a program for a certificate in public management and this involved meeting with Livingstone, who was going to talk to them about defense policy in the 21st century. The briefing was set to take place in a conference room on the fifth floor of the Pentagon’s E ring and was supposed to begin at 9:00 a.m. [26]

Livingstone and her executive assistant, Captain Dennis Kern, learned about the crashes in New York before the NSWC group arrived for the briefing. “Someone called to let us know two planes had hit the World Trade Center,” Kern recalled. [27] The NSWC employees, meanwhile, were delayed. Their bus was almost 20 minutes late and so they were traveling to the Pentagon when the attacks on the World Trade Center took place. They arrived at the conference room where the briefing was going to be held at about 9:10 a.m. At that time–around seven minutes after the second attack occurred–they were still unaware of the crashes in New York. But after they arrived, they were told what had happened. [28]

Livingstone said to them that “terrorists had attacked the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center in New York City just a few minutes earlier by hijacking two planes and flying them into the two towers,” according to Eric Moody, one of the NSWC employees. She also said that “she would have to cut her talk short due to another important meeting.” [29] Jim Buher, another member of the visiting group, recalled that Livingstone said, “I have to cut my presentation short today, because planes have hit the World Trade Center and I have to go to the Command Center at 9:30.” [30]

The members of the NSWC group were “all in shock” upon hearing the news, Dusty Wilson recalled. And yet Livingstone went ahead with the briefing. [31] She apparently discussed the information she’d originally intended to cover, without being influenced by what had happened in New York. Moody recalled that she talked about “her administration’s frustration stemming from the lack of effective strategic planning since the fall of the Berlin Wall.” [32]

Livingstone’s behavior appears to make no sense. Why did Livingstone continue with the briefing as if nothing abnormal had happened? Surely her attention should have been focused on dealing with the terrorist attacks. The meeting with the NSWC group could easily have been postponed. Furthermore, since the Pentagon was considered a likely terrorist target, surely Livingstone and Kern should have immediately arranged to get the NSWC group members moved to somewhere safer after they arrived at the conference room.

VISITORS WERE CONCERNED FOR THEIR OWN SAFETY

Some of the NSWC employees actually suspected they were in danger at the Pentagon after they learned what had happened at the World Trade Center. Greg Smith has commented, “It occurred to me, and probably others, that Washington, DC, would also be a terrorist target.” [33] Moody recalled that “it suddenly dawned on him that by sitting in the top military operations center in the country, the building they were in could be a targeted area.” [34] He said he had therefore thought his group “might be in danger” and had “said a short prayer, as I often do, ‘Dear God, please keep us safe.'” [35]

Doris Richardson was similarly concerned. She recalled: “I know I wasn’t the only one in that room who stopped to say a prayer. Mine went as it always does, ‘Lord, not my will but thine be done.'” [36] If these visitors realized the danger they were all in at the Pentagon, surely Livingstone and Kern should have too.

In fact, since Livingstone was the second-highest-ranking civilian in the Navy, it seems odd that her colleagues allowed her to remain on the top floor of the Pentagon’s outer ring–probably one of the most vulnerable areas of the building–when the U.S. was under attack. Why did no one come and take her to somewhere safer? Why did Kern, who, as her executive assistant, presumably bore some responsibility for her safety, allow her to go ahead with the briefing?

The conference room where the briefing took place was directly above the area of the building that was struck when the Pentagon was attacked. [37] It was “not more than 50 feet away from the area of impact,” according to Moody. [38]

When the Pentagon was hit–about 27 minutes after Livingstone’s briefing began–those in the conference room heard “a tremendous noise like dynamite” and felt the room rock. [39] Moody described: “A large blast shook the entire room. Several of the ceiling panels from the suspended ceiling fell to the floor and the light fixture in the middle of the room came crashing down on the conference room table. Smoke immediately began filling the room from the light fixtures and vents in the ceiling.” [40]

Although, by going ahead with the briefing, Livingstone had acted as if she was unaware of any danger to those at the Pentagon, when the building was hit she immediately realized what had happened. She told the others in the conference room, “It must be terrorists.” [41] Only then did she tell the group of NSWC employees to evacuate. Moody recalled that she “calmly but firmly stated that we were under a terrorist attack and we should immediately leave the building.” [42] Livingstone and Kern then led the NSWC employees out of the conference room. [43]

They all made it out of the Pentagon without injury. But Livingstone’s going ahead with the briefing when the U.S. was in the middle of a major terrorist attack could have had catastrophic consequences. “We all agree that we were extremely fortunate to survive this devastating situation,” Moody has commented. [44]

VICE CHIEF OF NAVAL OPERATIONS’ STAFFERS COULD ONLY ‘WATCH, LISTEN, AND PRAY’ AFTER THEY LEARNED OF THE CRASHES

We can see a pattern of military personnel failing to respond appropriately and effectively to the attacks on the World Trade Center when we examine the behavior of Navy staffers in some key spaces in the Pentagon. This pattern of behavior was, for example, exhibited by personnel in the office of Admiral William Fallon, vice chief of naval operations, on the fourth floor of the E ring.

When the attacks on the World Trade Center took place, Fallon was in the meeting in Vern Clark’s office, down the hallway from his own office, in which budget issues were being discussed. [45] But members of his staff were in his office, available to respond to the crashes.

One of them, Captain William Toti, special assistant to the vice chief of naval operations, learned of the first crash from the coverage of it on television. It occurred to him immediately that the crash must have been a deliberate act. He has commented that he and his colleagues “knew from the first moments that it was an act of terrorism.”

However, instead of taking action to initiate a military response, they started discussing where the terrorists would strike next if an organized attack was taking place. (Toti actually concluded that the terrorists would attack the Pentagon.) Seeing the second crash on television “confirmed what we already knew,” Toti has commented. And yet the staffers still did nothing toward implementing a military response. [46]

Lieutenant Kelly Ennis, aide-de-camp to the vice chief of naval operations, has confirmed the lack of response among Fallon’s personnel. Ennis had gone across the hallway from his own office to Fallon’s office in time to see the second hijacked plane crashing into the World Trade Center live on television. “All I could think is that we needed to get some help in New York,” he has commented. And yet, he said, “All we could do at that time was watch, listen, and pray for our family members there.” [47]

Toti even found time to call his wife. He recalled that because he knew the country was under attack and the Pentagon was a likely target, he wanted to call her while he still had a chance. She was not at home so he left a message telling her “to take the kids out of school, stay at home, and leave the phone lines open.” [48] But why did Toti call his wife when the U.S. was in the middle of a serious terrorist attack? Surely he should have realized that the promptness of the military’s response might determine whether any further attacks were successful and so his attention needed to be focused on his military duties. Surely phoning his wife could have waited?

As well as apparently failing to take action toward implementing a military response to the attacks in New York, it seems that Fallon’s staffers did not go down the hallway to check that their boss knew what was going on or bring him back to his office. In fact, considering that Fallon’s staffers supposedly realized “from the first moments” that the crashes in New York were “an act of terrorism” and had determined that the Pentagon was likely to be the next target, surely they should have been concerned that, in an office on the fourth floor of the Pentagon’s outer ring, Fallon might be in danger. And so surely they should have wanted to move such an important official to a safer location.

And yet it appears they did nothing toward that end. Rear Admiral William Crowder, Fallon’s executive assistant, only left Fallon’s office and went down the hallway to talk to the vice chief of naval operations about what was happening just before the Pentagon was hit–about 30 seconds before the attack occurred, according to Toti. [49]

OFFICER WAS TOLD TO KEEP QUIET ABOUT THE SUSPICIOUS PLANE FLYING TOWARD WASHINGTON

Toti’s recollections of the events of September 11 reveal other examples of suspicious behavior exhibited by Navy personnel. For example, after he saw the second crash on television but before the Pentagon was hit, Toti was concerned that the Navy Command Center had not called his office to provide it with information about what was happening. Someone from the Command Center finally contacted his office just before the Pentagon was attacked.

But why did it take them so long to get in touch? Surely Command Center personnel should have wanted to promptly tell Navy officers what they knew about the crisis. Toti certainly appears to have found their failure to contact his office odd: Just before the Command Center called, he was about to head there to find out what was going on, but was stopped by Crowder. [50]

Another suspicious incident occurred when the person at the Command Center contacted Fallon’s office. Crowder answered the call from the Command Center and was informed that a hijacked plane was heading toward Washington, DC. Commander David Radi, deputy executive assistant to the vice chief of naval operations, listened in on the call, as he was required to do, and so he heard the news. However, Crowder then instructed Radi: “That’s close hold. Don’t tell anybody what you just heard.”

Why did he say this? Surely it was imperative that people at the Pentagon be informed that a suspicious plane was heading in their direction, so they could mount a defense against an attack or get out of their offices and move to somewhere safer.

Toti has noted the oddness of Crowder’s request. “In retrospect, I wonder what the hell was close hold about that fact that there was a hijacked airplane coming in towards the Pentagon. If anything, it would have been nice to alert people of that,” he commented. “That stuck out in [my] mind at the time as kind of a peculiar thing [for Crowder] to say,” he added. [51]

COMMAND CENTER PERSONNEL CONTINUED THEIR USUAL WORK AFTER LEARNING OF THE CRASHES

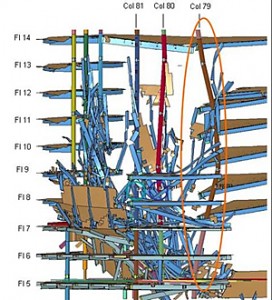

Another area of the Pentagon where personnel failed to respond appropriately and effectively to the attacks on the World Trade Center is the Navy Command Center. The Navy Command Center was on the first floor of the D ring, on the Pentagon’s southwest face. It was manned 24 hours a day by 40 to 50 people.

The Command Center played an important role in the Navy’s operations. It was “the sophisticated, round-the-clock hub that monitors Navy activities, plots movements for 317 ships, and keeps an eye on political events around the world,” according to the Washington Post. Timothy Keating described it as “a nerve center.” [52]

Its mission was “to constantly monitor global events while keeping up with the latest status of all U.S. naval assets operating worldwide,” according to Lieutenant Kevin Shaeffer, an action officer in the Navy’s Strategic Concepts Branch. Staffers in the Command Center were responsible for “keeping our Navy leadership updated with exactly what’s happening in the world, as it directly relates to Navy operations and other geopolitical security and military issues,” Shaeffer said. [53]

The Chief of Naval Operations Intelligence Plot (CNO-IP) was housed in the Command Center. The CNO-IP was responsible for keeping “a round-the-clock watch on geopolitical developments and military movements that could threaten American forces,” according to the Washington Post. [54]

And yet, despite their capabilities and responsibilities, personnel in the Command Center apparently did not immediately learn that a suspected hijacking was taking place on September 11. American Airlines Flight 11 was hijacked at around 8:14 a.m. that day, according to the 9/11 Commission Report, and between 8:25 a.m. and 8:32 a.m., managers at the Federal Aviation Administration’s Boston Center started notifying their chain of command that a suspected hijacking was in progress. [55] But while this was going on, it was just a “routine morning” in the Command Center, according to journalist and author Steve Vogel. [56]

Command Center staffers only learned something was wrong at the same time as the public did. A member of staff in the center noticed the coverage of the burning World Trade Center on television and promptly alerted his colleagues to it. People then quickly gathered around the center’s television sets. [57] The images from New York “held the attention of every individual in the bustling center,” Shaeffer recalled. [58] When the second hijacked plane hit the World Trade Center at 9:03 a.m., “a tense, audible gasp erupted throughout the space,” he said. [59] Those in the Command Center “knew it wasn’t an accident.” [60]

STAFFERS RETURNED TO THEIR DESKS

Sometime after the second crash occurred, someone in the Command Center said out loud, “This is war.” [61] And yet the actions of the center’s personnel were hardly what we might reasonably have expected from military staffers who considered themselves to be at war. Those in the Command Center appear to have taken no action toward implementing a military response to the attacks in New York and they seem to have acted with an astonishing lack of urgency, considering they were in a situation where anything could happen next and the speed of their reaction might determine whether any further attacks succeeded.

According to the Washington Post, even though a “few old hands muttered to themselves that the Pentagon was probably next” when they saw the coverage of the burning World Trade Center on television, “work had to continue.” Therefore, Shaeffer recalled, “As the minutes passed, most of us returned to our desks.” [62] Instead of responding to the crashes, it appears that many Command Center personnel continued with their usual duties and were still doing so when the Pentagon was hit, 48 minutes after CNN first reported that a plane had hit the World Trade Center.

For example, after he saw the second crash on television, Shaeffer “returned to his cubicle, where he and his three neighbors spent a few minutes discussing what they’d seen,” according to the Virginian-Pilot. They “wondered aloud how many people worked in those buildings, whether they were still straggling in when the planes hit. … What was it like inside those towers right now?” Even though Shaeffer thought the crashes were an “attack on American soil,” he apparently intended to continue his usual duties as if nothing abnormal had happened. “He tried to return to work,” the Virginian-Pilot reported, although he “couldn’t keep his mind on it.” [63]

Another staffer, Wallace “Trip” Lloyd, watched the coverage of the attacks on television for some time, according to his own recollections, and then “went back to my desk and sat down, getting ready to do some financial work.” [64] But why would Shaeffer and Lloyd want to continue with their usual work when their country was under attack? Surely responding to the crashes should have been their only concern.

STAFFERS MADE UNNECESSARY PHONE CALLS

Furthermore, after they saw the second crash on television, some of the personnel in the Command Center were “intent on calling loved ones,” Shaeffer has written. [65] For example, Petty Officer Charles Lewis “frantically tried to call his mother,” according to the Chicago Tribune. [66] And yet, under the circumstances, surely everyone should have been focused on their military duties. Calling relatives could have been put off until the crisis was over.

Similarly, just before the Pentagon was hit, Jarrell Henson, who was in charge of a seven-person staff in the Command Center “that coordinated Navy efforts in counterdrug operations and emergency relief,” made a call to cancel a hotel reservation. [67] Henson described, “I had just come from [the Office of the Secretary of Defense] about the budget events that were fairly significant, so I picked up the phone and called down to Norfolk, to the Hampton Inn, to cancel a reservation for a meeting that we had planned.” [68] But why did Henson carry out such an unimportant task–something he could have done at any time–in the middle of a terrorist attack, when every minute was precious?

Another person in the Command Center, Richard Sandelli, who worked for a Navy anti-drug task force, appears to have responded to the attacks on the World Trade Center with an alarming lack of urgency. Sometime after the second crash occurred, he received a call from the Army Operations Center (AOC) at the Pentagon, in which he was asked to come to the center. The AOC, Sandelli has said, “coordinates Department of Defense assets to assist civilian tragedy, and the Army Operations Center asks each service to provide a member to come down to their office and coordinate that service’s specific … assets to assist the folks in New York City, which they expected would happen based on the events.” Sandelli was therefore wanted at the AOC as a representative of the Navy.

Sandelli told the caller that he would report to the AOC at “about 9:45,” as he “wanted to make sure there were additional personnel to help us down in the Navy Operations Center and downstairs in the Army Operations Center, and I wanted to make a few last phone calls.” In other words, he said he would arrive in the AOC around 42 minutes after the second World Trade Center tower was hit. This hardly seems to be the level of urgency we might reasonably expect at a time when the U.S. was under attack.

Sandelli even spared several minutes to talk on the phone with his wife. At around 9:15 a.m. to 9:20 a.m., she called him because she wanted to know if he had seen what was on the news. Sandelli recalled that he and his wife “talked for a few minutes.” [69]

ROUTINE MEETING CONTINUED AFTER ITS ATTENDEES LEARNED OF THE CRASHES

Individuals who were attending a staff meeting in a conference room in the Command Center also appear to have reacted to the news of the crashes in New York with an alarming lack of urgency. Lieutenant Commander Dale Rielage, deputy executive assistant to the director of naval intelligence, who was in the meeting, recalled, “The usual routine of the meeting was quickly interrupted as the intelligence watch brought news of the successive attacks on the World Trade Center.” But instead of ending immediately in response to the events in New York, according to Rielage, the staff meeting continued until 9:30 a.m.–27 minutes after the second crash occurred. [70]

Why did Rielage and those with him continue their meeting when they should have responded immediately to the attacks? And why did no one else come into the conference room and insist that they end the meeting at once so as to deal with the attacks?

Furthermore, despite the important role the Command Center played in the Navy’s operations, personnel there apparently received no orders from their department’s top officials about what they should do in response to the attacks on the World Trade Center. According to Shaeffer, “Events were happening so quickly that no formal tasking on exactly what to do came down.” [71] And yet over 50 minutes passed between the first hijacked plane crashing into the World Trade Center and the Pentagon being hit. Surely that was more than enough time for senior Navy officials to issue the center’s personnel with “formal tasking on exactly what to do.”

SOME STAFFERS TRIED TO GATHER INFORMATION ABOUT THE CRASHES

At least a few staffers in the Command Center are reported to have taken action in response to the crashes at the World Trade Center. However, it appears that the most any of them did was try to gather information about what had happened, and they seem to have had only limited success in their efforts.

For example, according to Shaeffer, the Command Center “stood up a watch team to start logging events and tracking things for the Navy” after personnel there learned of the first crash. [72] Just before the Pentagon was hit, Shaeffer noticed that the “watch section and watch leaders” were still “actively engaged in logging and recording the events in New York City.” [73]

Meanwhile, Petty Officer Jason Lhuillier and his colleagues in the CNO-IP were “soon building the intelligence picture and liaising with the CIA, Defense Intelligence Agency, National Security [Agency], and the U.S. Navy’s sister services” after they learned of the second crash, according to the London Telegraph. [74] However, when David Radi called the CNO-IP sometime after the second crash occurred and asked, “What do we know?” all he was told was, “We’re working it.” [75]

Lieutenant Nancy McKeown, who was in charge of the Meteorology and Oceanography section of the Command Center, instructed her technicians, Petty Officers Edward Earhart and Matthew Flocco, “to bring up their computers and to start doing some research to see what we could find out” about what had happened, after she saw the television coverage of the burning World Trade Center. However, it is unclear how much relevant information the two technicians were able to discover. McKeown has only said that just before the Pentagon was hit, Flocco and Earhart were still “diligently working.” [76]

And Seaman Sarah Cole reportedly “knew her superiors would want more information” after she heard about the crashes at the World Trade Center, “so she began downloading photos from the Internet.” [77]

Like other Navy personnel at the Pentagon, those in the Command Center received no instructions to evacuate. Sometime after the second crash occurred, Jarrell Henson was called by his wife, who asked him if he and his colleagues had “gotten any advice to vacate or to get out of the building.” Henson told her, “No, everything is being reacted to here, but we haven’t had any guidance yet.” [78]

Unfortunately, the failure to evacuate had tragic consequences. Much of the Navy Command Center was destroyed in the attack on the Pentagon. [79] All of the 42 Navy employees at the Pentagon who died in the attack were in the Command Center. Only eight of the 50 people who were in the Command Center when the Pentagon was hit survived. [80]

COMMANDER TOLD HIS STAFFERS TO ‘GET A CUP OF COFFEE TOGETHER’ AFTER LEARNING OF THE CRASHES

Accounts of the actions of numerous individuals, in addition to those mentioned above, provide more evidence that Navy personnel at the Pentagon consistently failed to respond appropriately and effectively to the attacks on the World Trade Center. These accounts describe Navy staffers acting with an alarming lack of urgency after they learned of the crashes, doing little if anything toward implementing a military response to them, and continuing their normal activities as if nothing unusual had happened.

A good example is the account of Commander Frank Thorp, special assistant for public affairs to the chief of naval operations. Thorp was in his office at the Pentagon when the World Trade Center was attacked. But even though he had seen the coverage of the burning Twin Towers on television, he instructed his staffers to resume their usual duties. “After some period of time watching it,” he described, “I came to realize, ‘Hey, we’ve got this big project due.'” He therefore told his staffers, “Hey, everybody, let’s get back to work.”

Thorp then continued to act without any urgency. “For the first time in my life, I said, ‘But first, let’s all go get a cup of coffee together,'” he recalled. Thorp and his workers therefore “got up … walked out of the office, walked down the hallway, and the plane hit [the Pentagon] about a tractor-trailer’s length away from my office.” [81]

STAFFERS DECIDED ‘WE NEEDED TO GET BACK TO OUR JOB’ AFTER THEY REALIZED ‘IT WAS A TERRORIST ATTACK’

Navy personnel in room 4C453, on the fourth floor of the C ring, also continued their usual duties after they learned of the attacks on the World Trade Center.

Commander Joan Zitterkopf, a helicopter pilot assigned to a training aircraft redesign group who was in room 4C453 on September 11, recalled that she learned about the first crash when “the chief came out of the admiral’s outer office and said he’d gotten a phone call [in which he was told] that there had been an airplane crash into the World Trade Center.” The person who’d called, who was in the Navy Command Center, had wanted to know if Zitterkopf’s department was missing an aircraft and had wondered if the plane that hit the World Trade Center could be one of theirs.

The television in Zitterkopf’s office was then turned on and about eight members of staff subsequently saw the second hijacked plane hitting the World Trade Center as it happened. “There was just [a] kind of a gasp in the room because, obviously, we knew at that point in time [that] it was a terrorist attack,” Zitterkopf recalled. She and her colleagues “were relatively dumbfounded” and “watched in almost a silent horror for a few minutes.” And yet they then “decided we needed to get back to our job.” Zitterkopf returned to her desk and started preparing for a previously scheduled meeting that was set to take place at 11:00 a.m.

Zitterkopf was then called to the front office to discuss whether the 11:00 a.m. meeting should be rescheduled. Some senior Navy officers who were in a meeting downstairs were on the phone. “They were trying to decide whether we were going to continue with our meeting or whether we were going to do something different,” Zitterkopf described. She said she “thought we should cancel the meeting until things calm down.” However, Zitterkopf recalled: “They said: ‘No, we’re going to go ahead and have the meeting. Call down to the people that are coming and tell them we’re going to go ahead with the meeting.'” (It is unclear from Zitterkopf’s account if the people who said this were the senior officers in the meeting downstairs or some co-workers who were with Zitterkopf in the front office.) [82]

But how could anyone have decided to go ahead with a previously scheduled meeting that was unrelated to the crashes in New York at such a critical time? Surely, those organizing the 11:00 a.m. meeting should have wanted Navy personnel to focus all their attention on dealing with the attacks, without having to worry about attending any unnecessary meetings.

AIR WARFARE DIVISION PERSONNEL ‘WENT BACK TO WORK’ AFTER WATCHING THE TV COVERAGE OF THE CRASHES

Like Zitterkopf and her colleagues, Navy personnel in room 5D453, on the fifth floor of the D ring, appear to have continued their usual work after they learned of the crashes at the World Trade Center.

In this office, where most of the Air Warfare Division’s spaces were located, Captain Timothy Tibbits and his colleagues had been watching the television coverage of the first crash and then saw the second crash live at 9:03 a.m. They then “knew that things had just changed for the worse and that the day would be a long one in the Pentagon,” Commander Don Braswell described. Some of the staffers expressed concern that the Pentagon might be attacked. “[A] few bubbas had mentioned that the Pentagon, White House, and the Capitol building were probably targets,” Braswell recalled.

And yet those in room 5D453 apparently did nothing toward implementing a military response to the attacks on the World Trade Center, and they made no moves toward getting out of their office and to somewhere safer. Instead, it appears they eventually just returned to their normal duties. “They stared at the [television] set for a half-hour, and asked why it happened and how it happened,” the Everett Herald reported. “Then, everyone went back to work.”

Room 5D453 was directly above the area of the Pentagon that was hit at 9:37 a.m., and when the attack took place, the office’s floor shook and “a huge explosion sucked the air out of the room.” [83]

OFFICER PLANNED HIS DAILY RUN AFTER BEING TOLD THE U.S. WAS UNDER ATTACK

Captain Tom Joyce, a deputy for naval aviation, also returned to his usual duties after he learned of the crashes at the World Trade Center and even spent time planning his daily run, instead of taking action in response to the attacks. His apparent indifference to what happened in New York is astonishing.

Joyce, who worked in an office on the fifth floor of the D ring along with about 100 other people, learned about the attacks on the World Trade Center from the coverage on television. After those in his office saw the second crash on TV, one of his colleagues called a friend in the Pentagon’s National Military Command Center and asked him what he knew. The friend said: “We’ve got other planes that are hijacked. We’re under attack. We don’t know from who.” Joyce and his colleagues looked at each other and said, “We’ve got to be a target [at the Pentagon].”

All of the admirals who worked in Joyce’s office were away for a meeting and so Joyce was “the senior guy” in the office at the time. And yet he then continued his normal duties as if nothing unusual had happened. “What do you do?” he has commented. “We were there to work that day and I went back to work.”

Joyce phoned his wife, to tell her what was going on. Then he spent time thinking. “I tried to focus my thoughts on what might happen and what our responses should be in various scenarios,” he recalled. At that time, Joyce would go for a daily run in the area around the Pentagon. So he also spent time “just looking out the window and kind of mapping in my mind my route” for his run that day. The reason he did this, he said, was, “I just needed to clear my mind from everything I had seen on TV.”

Joyce was still looking out the window, planning his run, when the Pentagon was hit. His office was directly above the area of the building that was struck and some of his colleagues were injured by debris that flew across the room as a result of the impact. [84]

OFFICER STARTED DOING RESEARCH FOR A PROJECT AFTER HE LEARNED OF THE CRASHES

Chief Warrant Officer John Gregorowicz similarly continued his usual work after he learned of the attacks on the World Trade Center. Gregorowicz, who was temporarily stationed at the Pentagon so as to organize a meeting of navies from around the world, learned of the crashes at the World Trade Center from the coverage on television. “It was unbelievable what we saw on TV,” he has commented. And yet he carried on with his work as if nothing out of the ordinary had happened. “We could only watch so much of it, I guess,” he said, and so he “just went back to work and started to do some research on my project that I had to do there.”

Gregorowicz subsequently left his office in the A ring and headed toward the C ring to get a cup of coffee. The Pentagon was hit as he was leaving the A ring and he saw “a fireball coming right down the quarter right at us.” [85]

Jim Stewart, a Navy staff assessment director, and his colleagues, who were in an office on the fourth floor of the C ring, also appear to have carried on with their normal duties and done nothing toward implementing a military response after learning of the crashes at the World Trade Center. After Stewart learned of the crashes, he took the time to phone his wife to tell her what had happened. And, he has recalled, although they thought what had happened was “horrendous,” he and the other people in his office were “trying to carry on with their responsibilities” when their building was attacked at 9:37 a.m. [86]

INTELLIGENCE OFFICER WENT AHEAD WITH A PRESENTATION DESPITE KNOWING ABOUT THE ATTACKS

Tanya Edwards, who worked for the director of naval intelligence, apparently continued with her scheduled activities after she learned about the crashes in New York. On the morning of September 11, she was attending meetings in the Pentagon related to the movement of the intelligence staff while the Pentagon was being renovated. She knew about the attacks on the World Trade Center, having seen the coverage of them on television. And yet she went ahead with a presentation that was apparently unrelated to the crisis that was taking place. “When the plane hit [the Pentagon],” Edwards recalled, “I was giving a presentation to several different divisions, and many of us fell to the floor because of the impact of the plane hitting the building.” [87]

Meanwhile, an officer went ahead with a reenlistment, despite having just spent time following the television coverage of the attacks. Dewitt Roseborough, the chief of naval operations’ photographer, has recalled that he was covering a reenlistment in the secretary of the Navy’s mess at the Pentagon on September 11. The reenlisting officer was running 20 minutes late that morning because he had been watching CNN’s coverage of the crashes in New York. When the officer finally arrived at the mess, at 9:20 a.m., he told the people assembled there what had happened at the World Trade Center. And yet he then continued with his work as if nothing out of the ordinary had happened. Roseborough recalled that even though “there were a lot of people in shock, we proceeded with the reenlistment.” [88]

TRAINING DIRECTOR’S PERSONNEL WATCHED ATTACKS ON TV BUT DID NOT RESPOND TO THEM

As a final example of the Navy’s inaction on September 11, Navy employees who worked for Allen Zeman, director of naval training and education, appear to have done practically nothing in response to the attacks on the World Trade Center and instead spent their time watching the television coverage of the crashes.

Christopher Howk, an administrator who worked for Zeman, was at his desk when his wife called and alerted him to the first crash. He then went with some colleagues into Zeman’s office to watch the television coverage of the crash and saw the second crash when it occurred. Howk has recalled that he and his colleagues then realized that what had happened “wasn’t possibly a mistake.” A lieutenant in the room commented, “I wonder when we’re going to get hit [at the Pentagon]?”

And yet Howk and his colleagues, who were responsible for planning the movement of Navy personnel, appear to have taken no action toward implementing a military response to the crashes. Instead, they just speculated about what the Navy might do. “We stayed glued to our posts in the office and discussed how we’d ‘spin the fleet up’ to do what was needed,” Howk said.

When one of their co-workers, Yeoman Melissa Barnes, arrived at work at 9:30 a.m., she found her office was “mysteriously empty.” At that time–only seven minutes before the Pentagon was hit–all of her colleagues were huddled around the television in Zeman’s office. “[E]veryone in the office was standing there watching,” All Hands magazine reported. [89]

SOME STAFFERS JOKED ABOUT THE POSSIBILITY OF THE PENTAGON BEING HIT

As well as failing to initiate a military response to the attacks and continuing with their usual duties, Navy personnel reacted inappropriately in other ways after they learned about the crashes at the World Trade Center. Some of them actually joked about the possibility of the Pentagon being attacked.

Joan Zitterkopf described an example of this behavior. “I remember distinctly, at one point in time, someone commenting that the roof of the Pentagon was five concentric circles,” she recalled. In response, she had “joked and said, ‘Yeah, if we painted them red, we’d just be a big bull’s-eye!'” Zitterkopf recalled that she and her colleagues “joked about [the fact that] we probably were ‘sitting in the middle of a bull’s-eye,'” and then “went on back to what we were doing.” [90]

Timothy Tibbits described another such incident. He said that, at some point after the World Trade Center towers were hit, his father-in-law left a phone message for him, in which he advised Tibbits to turn on a television and warned, “I don’t know if anybody’s talking about it, but the Pentagon could be a target.” Tibbits recalled that “the warning made his co-workers laugh.” [91]

This is baffling. Why would Navy staffers laugh about the attacks when many people had just been killed at the World Trade Center and the lives of those at the Pentagon might be in danger?

OVER 40 NAVY STAFFERS DIED IN THE PENTAGON ATTACK

The attack on the Pentagon at 9:37 a.m. on September 11 had catastrophic consequences for the Navy. The department lost 70 percent of its offices in the Pentagon as a result of the attack. [92]

The Navy Communications Center and the Navy Budget Office were totally destroyed, while the Navy Command Center was mostly destroyed. [93] According to William Toti, “The Navy was reduced to 11 percent of its footprint.” Percentage-wise, this was “by far the biggest hit of any service or agency” at the Pentagon. [94]

Tragically, 42 Navy personnel were killed–about a third of the 125 Department of Defense employees who died in the attack on the Pentagon. [95]

Remarkably, considering the apparently poor response of Navy personnel at the Pentagon to the crashes at the World Trade Center, Admiral Robert Natter, commander of the Navy’s Atlantic Fleet at the time of the 9/11 attacks, claimed that on September 11, the Navy was “responsive to something that came out of the clear blue” and “naval forces reacted to it the way the taxpayers would have wanted.” Vern Clark claimed that the Navy was “thinking about the immediate protection of the United States of America” that day. [96]

THE NAVY HAD FIGHTERS AVAILABLE BUT PROVIDED NO AIR DEFENSE OVER NEW YORK AND WASHINGTON

The poor response of Navy personnel at the Pentagon to the attacks on the World Trade Center is particularly noteworthy considering that the Navy had fighter jets that may have been able to provide air defense over New York and Washington, DC. This fact alone should have necessitated that Navy personnel respond as quickly as possible to the crisis on September 11.

In fact, if the Navy was indeed capable of providing fighters to protect these cities, this gives rise to the possibility that, had it been alerted to the hijackings quickly enough, its aircraft might have stopped at least one or two of the attacks that day. And yet the Navy apparently failed to provide any air cover over New York and Washington on the morning of September 11.

The Navy had fighters at Naval Air Station Oceana in Norfolk, Virginia, at Naval Air Facility Washington, DC, about 10 miles from the capital, and at Naval Air Station Patuxent River in Maryland, 65 miles southeast of the Pentagon. At NAS Oceana, F-14 Tomcats and F/A-18 Hornets were available. [97] At NAF Washington, F/A-18 Hornets were available. [98] And at NAS Patuxent River, F/A-18E Super Hornets were available. [99]

Rudy Washington, one of New York’s deputy mayors, clearly seems to have thought the Navy was capable of protecting the airspace over his city. Immediately after he first saw the burning World Trade Center as he was being driven into downtown Manhattan on September 11, he called Robert Natter and requested air cover over New York. [100]

Washington told Natter, “I need some air protection here.” Natter has recalled that in response to Washington’s request, he “had the staff call out to Naval Air Station Oceana, where we have our fighters based, and told them to arm some of the fighters with Sidewinder missiles.” [101] However, it is unclear whether any of the Navy’s fighters arrived over New York that morning. [102]

And Captain G. J. Fenton, who was at NAS Patuxent River at the time of the 9/11 attacks, has indicated that his base may have been able to provide fighters to protect the airspace over Washington and the Pentagon. Fenton recalled that he “was assigned the task of providing air defense for Patuxent River” on September 11. Although, he said, “most of our aircraft weren’t configured to fire live missiles or shoot live guns” and the base only “had a total of two live A-9 Sidewinders to mount on our aircraft,” personnel at the base “set up a few aircraft to be launched at a moment’s notice to defend us in case we were called.” “Our nation was under attack and we had some tools to do something about it in case the attacks continued,” Fenton commented. [103]

Since NAS Patuxent River was capable of providing at least some air defense for its surrounding area, then, could it have provided air defense for Washington and the Pentagon, as it was only 65 miles from the capital? And might it have been able to get some of its fighters airborne before the Pentagon was hit?

THE NAVY HAD MANY ASSETS IT COULD USE TO DEFEND THE U.S.

The extent of the Navy’s capability to respond to a crisis like the 9/11 attacks becomes clearer when we read a couple of accounts that describe the actions the Navy took later on the day of September 11, apparently after the attacks were over. These accounts highlight the significance of the lack of response of Navy personnel at the Pentagon to the crashes at the World Trade Center. They show that the Navy had numerous assets it could use to protect the U.S. It was therefore imperative that Navy personnel respond immediately to the crisis, so these assets could be called into action as quickly as possible.

One of the accounts is a speech given by Vern Clark in March 2002. On September 11, Clark said, “Cruisers and destroyers with the Aegis weapon systems immediately took off from Washington, DC, and then moved up to New York to provide for air defense.” Navy radar aircraft also “took to the skies immediately.” [104]

The other account, an article in Sea Power, described: “The aircraft carrier USS George Washington, operating off the Virginia Capes, was dispatched to New York following the recovery of armed F-14 Tomcats and F/A-18 Hornets from Naval Air Station Oceana, Virginia. The carrier USS John F. Kennedy, departing Mayport, Florida, was ordered to patrol the waters off Hampton Roads, Virginia, to protect the Navy’s vast shore complex in Norfolk.”

“Within three hours,” Sea Power reported, “an undisclosed number of Aegis guided-missile cruisers and destroyers also were underway, their magazines loaded with Standard 2 surface-to-air missiles.” These warships, which were positioned off New York and Norfolk, and along the Gulf Coast, “provided robust early-warning and air defense capabilities to help ensure against follow-on terrorist attacks.” Additionally, as well as launching fighters, the Navy “pressed into service” E-2C Hawkeye early warning aircraft “to monitor U.S. airspace.” [105]

NAVY PERSONNEL RECEIVED NO ORDERS TO EVACUATE

An aspect of the Navy’s lack of response to the crashes at the World Trade Center that deserves particular attention is the failure of Navy personnel at the Pentagon to evacuate from their building before it was attacked. As well as making no attempt to get out of their own accord, Navy personnel, like everyone else at the Pentagon, received no orders to evacuate before the attack took place, at 9:37 a.m. [106] An order to evacuate only went out over the Pentagon’s public address system shortly after the building was hit. [107]

A document published by the Defense Protective Service–the law enforcement agency that guards the Pentagon–in October 2001 outlined who was responsible for ordering an evacuation. It stated, “Normally, the decision to activate the Pentagon evacuation plan is made by the director, Washington Headquarters Service (WHS), or their designee, who is typically the on-duty watch commander for the Defense Protective Service.”

However, the document noted, “this does not preclude Department of Defense components from ordering an evacuation from their office spaces in the event of emergency.” Furthermore, the document stated, “Building occupants do not have to wait to evacuate” in an emergency. The overriding principle was that “common sense should prevail.” [108]

In other words, in line with official guidelines, senior Navy officials could have ordered their personnel to evacuate from the Pentagon and/or personnel could have evacuated of their own accord on September 11. Why then did no evacuation take place before the Pentagon was hit?

Defense Department officials blamed the failure to evacuate on “[c]onfusion, uncertainty, poor communication, and a general lack of preparedness,” according to the Washington Post. [109] Pentagon spokesman Glenn Flood tried to explain the failure, saying: “To call for a general evacuation at that point [i.e. after the second hijacked plane hit the World Trade Center], it would have been just guessing. We evacuate when we know something is a real threat to us.” He also said an evacuation could have put Pentagon employees at risk by moving them outside the protection provided by the building’s walls. [110]

But are these explanations credible, considering that on the morning of September 11 the U.S. was under attack, anything could have happened next, and those in the Pentagon could have been injured or killed if their building was a target–as it indeed turned out to be?

THE PENTAGON WAS REGARDED AS A LIKELY TERRORIST TARGET

The failure to evacuate any military personnel from the Pentagon before it was attacked is remarkable considering that, even before 9/11, the building was considered a likely target for terrorists. Several people have indicated that the danger was well known.

Christopher Howk, for example, commented, “We at the Pentagon know we’re one of the top targets in the country and [before September 11] we knew it wasn’t a matter of if, it was a matter of when [the Pentagon would be attacked].” Howk and his colleagues reportedly “knew the Pentagon, as headquarters of the world’s most powerful military as well as the world’s largest office complex, had been in the crosshairs of terrorists for years.” [111]

Stacie Condrell, a senior Pentagon Renovation Project planner, said in October 2001, “I have known for some time that the Pentagon was vying with some other building–the Capitol or the White House–for being the number one or two terrorist target in the world.” She said she assumed the Pentagon had been designated as one of the top terrorist targets “based on some actual intelligence that indicates the likelihood of attack.” [112]

Army Lieutenant Colonel Ted Anderson, a Congressional liaison, commented that before 9/11, “We had talked about what a tremendous target the Pentagon was and how vulnerable we were [at the Pentagon].” [113] And when Donald Rumsfeld–the secretary of defense on September 11–was asked if he had ever thought, before 9/11, that it was possible that terrorists would attack the Pentagon, he replied, “Obviously the Pentagon is a target, like any large important government building in the United States … so I had thought about those kinds of problems in general.” [114]

Furthermore, a software system commissioned by the Department of Defense had determined that the Pentagon “was in danger from a terrorist attack.” According to popular science writer Keith Devlin, the software, called Site Profiler, “worked by combining different data sources to draw inferences about the risk of terrorism” and “provided site commanders with tools to help assess terrorist risks so that they could develop appropriate countermeasures.”

Site Profiler’s developers “carried out a number of simulations, based on hypothetical threat scenarios.” [115] Their initial evaluation, conducted in 2000, “included a scenario involving a terrorist attack on the Pentagon by means of a mortar shot from the Potomac River.” In the evaluation, “the model results indicated that the Pentagon was vulnerable to terrorist attack.” [116]

SOME AT THE PENTAGON THOUGHT THEIR BUILDING MIGHT BE ATTACKED

Not only was the Pentagon considered a likely terrorist target, some people at the Pentagon actually said out loud, after they learned of the crashes at the World Trade Center, that they thought their building might be attacked next. For example, Vice Admiral Edmund Giambastiani Jr., Donald Rumsfeld’s senior military assistant, talked with Stephen Cambone, Rumsfeld’s closest aide, after the second hijacked plane hit the World Trade Center and the two men discussed whether the Pentagon might be struck as well. They talked about “the idea that the Pentagon could be a target,” according to Giambastiani. [117]

Christopher Howk recalled that one of his colleagues said, after seeing the second crash on television, “I wonder when we’re going to get hit [at the Pentagon]?” [118] Pentagon employee John King told his colleagues that the Pentagon was “probably the next target” after he saw the second crash on television. [119] Don Braswell recalled that, as they watched the television coverage of the crashes in New York, some of the Navy staffers with him “mentioned that the Pentagon, White House, and the Capitol building were probably targets.” [120] And Tom Joyce recalled that, after they saw the second crash on TV, he and his colleagues said to each other, “We’ve got to be a target [at the Pentagon].” [121]

Meanwhile, in the Navy Command Center, after they learned of the attacks on the World Trade Center, “A few old hands muttered to themselves that the Pentagon was probably next,” the Washington Post reported. [122] Paul Brady told two of his colleagues, “Well, I guess that we will be the next on their target list.” [123] And Charles Lewis heard a colleague say, “If it could happen there [i.e. at the World Trade Center], what could stop it from happening here?” [124]

In the office of the vice chief of naval operations, William Toti and his colleagues realized immediately that the first crash at the World Trade Center was an act of terrorism, and started discussing where the terrorists would strike next if the crash was part of an organized attack. Toti quickly determined that “the only building that makes sense is the Pentagon.” [125]

Furthermore, at some point after the second crash occurred, Army Deputy Administrative Assistant Sandra Riley phoned the chief of the Defense Protective Service and asked him, “What do we have in place to protect [the Pentagon] from an airplane?” So at least one person appears to have thought the Pentagon might be attacked from the air. (The chief of the Defense Protective Service reportedly replied, “Nothing.”) [126]

In fact, some Navy employees specifically thought that people needed to get out of the Pentagon. For example, when Yeoman Cean Whitmarsh, who worked in the office of the director of surface warfare, saw the television coverage of the crashes at the World Trade Center, “His first thought was that he needed to get out of the Pentagon,” according to the Fort Worth Star-Telegram. [127] And, after she learned of the crashes, Joan Zitterkopf said out loud: “I think we really ought to be getting out of here. I just don’t think we ought to be in this building.” [128]

PROTECTIVE SERVICE OFFICERS DID NOT INCREASE THE THREAT LEVEL AT THE PENTAGON

The failure to evacuate at least some people from the Pentagon before the attack there took place appears to make no sense. But one thing that may have been a factor in why no evacuation took place is the failure of the Defense Protective Service (DPS) to raise the threat level at the Pentagon following the attacks on the World Trade Center. The actions of senior DPS personnel in fact seem inexplicable.

John Jester, chief of the DPS on September 11, has stated that, after he learned of the crashes at the World Trade Center, even though he realized these crashes were a “terrible attack,” it didn’t occur to him that a similar thing could happen at the Pentagon. [129] Remarkably, after the second hijacked plane hit the World Trade Center, he instructed Lieutenant Michael Nesbitt, who ran the day-to-day operations in the DPS Communications Center, to send a message to the building’s Real Estate and Facilities Directorate, reassuring everyone that the Pentagon was secure and its Terrorist Threat Condition was staying at “Normal”–the lowest level on a five-tier scale–which meant there was no present threat of terrorist activity. [130]

Jester eventually issued the order to raise the state of alert at the Pentagon, but he only did this just before the building was attacked. And even then, he only ordered that it be raised one level. He instructed his deputy, John Pugrud, to tell the DPS Communications Center to raise the Terrorist Threat Condition from Normal to Alpha, which meant a general threat of possible terrorist activity existed that required enhanced security. It meant spot inspections of vehicles and increased police patrols were required. But Pugrud was still in the process of phoning the DPS Communications Center about raising the threat level at the time the Pentagon was hit. The Terrorist Threat Condition would therefore still have been at Normal when the attack occurred. [131]

The DPS’s failure to raise the threat level is particularly notable considering that official books and documents have indicated that the DPS had a key role to play in ordering the evacuation of the Pentagon. For example, as previously mentioned, a document published by the DPS in October 2001 stated, “Normally, the decision to activate the Pentagon evacuation plan is made by the director, Washington Headquarters Service (WHS), or their designee, who is typically the on-duty watch commander for the Defense Protective Service.” [132] (The director of the WHS on September 11 was David O. “Doc” Cooke, but it is unclear who the on-duty watch commander for the DPS was.)

A handout for Pentagon employees published by the DPS in August 2000 stated that the DPS was responsible for “[o]rdering evacuations, when circumstances require an evacuation and when an evacuation has not already been ordered.” [133] And the Department of Defense’s book about the Pentagon attack stated that the DPS, along with the Pentagon Building Management Office, was responsible for the “orderly evacuation” of the Pentagon. [134]

WHY DID THE NAVY RESPOND SO POORLY TO THE ATTACKS ON THE WORLD TRADE CENTER?

The failure of Navy personnel at the Pentagon to take action toward implementing a military response to the attacks or evacuate from their building after they learned of the crashes at the World Trade Center gives rise to many questions.

For example, why did Navy personnel apparently do so little in response to what had happened in New York, considering that the Navy, along with the rest of the U.S. military, was responsible for protecting America if it were attacked? Why did Navy personnel just watch the coverage of the crashes on television or phone their relatives when their attention should have been focused on responding to the crisis? Why did some of them continue with their normal duties as if nothing unusual had happened?

The accounts examined in this article indicate that Navy staffers received no orders from their department’s senior officials about what to do in response to the attacks on the World Trade Center. Why was this? Surely the Navy’s leaders should have taken charge of the situation immediately so as to ensure a prompt, coordinated, and effective response to the crisis.

Additionally, why was no attempt made to evacuate Navy personnel–or, indeed, anyone else–from the Pentagon before the attack there took place, especially considering that the building was regarded as a likely target for terrorists? And why were some Navy staffers able to joke about the possibility of the Pentagon being attacked? Surely they should have realized the seriousness of what had happened at the World Trade Center and that many people had just lost their lives. They should hardly have felt like joking.

DID NAVY PERSONNEL THINK THE CRASHES WERE PART OF AN EXERCISE?

A possible reason for the apparently inexplicable behavior of Navy personnel at the Pentagon is that these individuals mistakenly thought the reported attacks on the World Trade Center were simulations, as part of a training exercise.

Whether the Navy was conducting an exercise on September 11 is unknown. However, other military agencies are known to have been running or preparing for exercises at the time of the 9/11 attacks, which may have created confusion among their personnel over what was “real-world” and what was simulated. And Major Don Arias, the North American Aerospace Defense Command’s public affairs officer on September 11, has stated: “[I]t’s common practice, when we have exercises, to get as much bang for the buck as we can. So sometimes we’ll have different organizations participating in the same exercise for different reasons.” [135]

On the basis of this evidence, it certainly seems possible that, on September 11, the Navy was participating in one of the exercises run by other agencies or holding its own exercise that was intentionally scheduled to take place at the same time as other agencies conducted theirs.

AIR DEFENSE EXERCISE HAD SIMILARITIES TO THE 9/11 ATTACKS

The exercises conducted by other military agencies include “Vigilant Guardian,” which the North American Aerospace Defense Command was in the middle of running on September 11. This has been described as “an air defense exercise simulating an attack on the United States” and, two days before 9/11, it included a scenario in which terrorists planned to blow up a hijacked airliner over New York. [136] Therefore, since it had similarities to the 9/11 attacks, Vigilant Guardian presumably could have led to confusion among military personnel over what was real and what was simulated when those attacks took place.

Another exercise was “Global Guardian,” which the U.S. Strategic Command was in the middle of running on September 11. Global Guardian involved America fighting a fictional nuclear war. It “posited that a rogue nation called Slumonia would attack the United States with nuclear weapons,” according to journalists Eric Schmitt and Thom Shanker. [137]

And at the time of the 9/11 attacks, the Army was preparing an exercise for its Crisis Action Team at the Pentagon, which was set to take place in the week after September 11 and was based around the scenario of a plane crashing into the World Trade Center. [138] The existence of this exercise may well have caused confusion among Army staffers over what was real and what was simulated when planes crashed into the World Trade Center on September 11.

PARTICIPANTS IN AN ARMY EXERCISE THOUGHT THE TV COVERAGE OF THE ATTACKS WAS SIMULATED

If the Navy was indeed running or participating in a training exercise on September 11 and its personnel failed to respond to the attacks on the World Trade Center because they thought these were simulated, this would imply that Navy staffers thought the television coverage of the crashes was simulated, i.e. it was video that had been created to make the exercise feel more realistic. Although it might seem difficult to believe this could have happened, evidence indicates that it may have been the case. Specifically, reports have described how participants in one military exercise taking place on September 11 did indeed mistakenly think that television coverage of the crashes at the World Trade Center was video that had been created for their exercise.

At Fort Monmouth, an Army base about 50 miles south of New York, preparations were underway on the morning of September 11 for the exercise “Timely Alert II,” which was intended to test the base’s response to a biochemical terrorist attack. When the director of this exercise told a group of participating volunteers that a plane had crashed into the World Trade Center, the volunteers reportedly “pretended to be horrified and upset, never believing the story to be anything but part of the simulation” for the exercise. A senior officer at the base has recalled that “people on post told him, when they first saw live footage of the events unfolding at the World Trade Center, they thought it was some elaborate training video to accompany the exercise.” One person, referring to the television coverage of the crashes, told a fire department training officer, “You really outdid yourself this time.” [139]

If these people thought the television coverage of the attacks was video created for an exercise, surely Navy personnel at the Pentagon could have made the same mistake.

THE NAVY’S LACK OF RESPONSE MAKES SENSE IF PERSONNEL THOUGHT THE ATTACKS WERE PART OF AN EXERCISE

If the Navy was running or participating in a training exercise on September 11, this could help explain the apparent lack of urgency of its personnel at the Pentagon after they learned about the crashes at the World Trade Center, since these individuals may have mistakenly thought the crashes were a simulated scenario in the exercise.

For example, if Navy personnel thought the crashes were simulated, they presumably would have felt it was unnecessary to promptly implement a military response to them, and this could be why they failed to take action immediately. They may also have felt they had time to phone their relatives–as some of them did–even though, in reality, their attention should have been focused on dealing with the crisis.

Navy personnel who knew an exercise was taking place but were not participating in it themselves would presumably have felt it was alright to carry on with their usual duties, as some of them did, since the exercise–unlike a real-world attack–was of no concern to them.

Personnel would have felt it was unnecessary to get out of the Pentagon if they thought the reports indicating that America was under attack were part of an exercise. If they thought the reported attacks were just simulated, they would have felt they were safe at the Pentagon, even though the building was considered a likely target for terrorists.

They would also presumably have felt it was acceptable to make jokes about the Pentagon being a possible target, as some of them did, since they would have thought no one had actually died at the World Trade Center and they were in no real danger at the Pentagon.

And if senior Navy officials thought the reported attacks were simulated, they may have failed to promptly issue orders to their personnel regarding how to respond because they felt it was unnecessary to do so simply for an exercise.

INVESTIGATORS NEED TO PROBE THE ACTIONS OF NAVY PERSONNEL ON SEPTEMBER 11

The actions of Navy personnel at the Pentagon on September 11, 2001, need to be examined as part of a new investigation of the 9/11 attacks, so as to address questions like those raised in this article. In particular, the possibility that the Navy was involved in a training exercise on September 11 should be investigated.

If the Navy was indeed participating in or running an exercise that day, investigators need to find out exactly what the exercise involved. They also need to examine whether it prevented Navy staffers from effectively responding to the terrorist attacks, such as by causing them to mistake actual events for a simulated scenario.

Additionally, investigators should consider whether rogue individuals in the U.S. military were involved with preparing and running the exercise. Such individuals could have intentionally designed and arranged an exercise that would create confusion, and ensure that honest military personnel were unable to stop the 9/11 attacks before the targets in New York and Washington were hit.

By addressing these issues, investigators will take us closer to knowing the full truth about what happened on September 11 and who was responsible for the attacks that day. Crucially, by doing so, they will help bring the perpetrators to justice.

NOTES

[1] Gordon I. Peterson, “Bush: ‘The Might of Our Navy is Needed Again.’ Readiness Improvements Prove Critical in War on Terrorism, but Future Navy is at Risk.” Sea Power, January 2002.

[2] Alfred Goldberg et al., Pentagon 9/11. Washington, DC: Historical Office, Office of the Secretary of Defense, 2007, p. 134.

[3] Sylvia Adcock, Brian Donovan, and Craig Gordon, “Air Attack on Pentagon Indicates Weaknesses.” Newsday, September 23, 2001; Steve Vogel, The Pentagon: A History. New York: Random House, 2007, p. 429.

[4] William Toti, interview by Mike McDaniel. U.S. Naval Historical Center, October 10, 2001.

[5] Alfred Goldberg et al., Pentagon 9/11, p. 34.

[6] Gordon I. Peterson, “Bush: ‘The Might of Our Navy is Needed Again'”; Vern Clark, “Meeting the Homeland Defense Challenge: Maritime and Other Critical Dimensions.” Remarks at the Institute for Foreign Policy Analysis and the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, Cambridge, MA, March 26, 2002; “Regent Remembers 9/11.” Impact, September 2011.

[7] Tom Bowman, “Joint Chiefs Nominee Mullen a ‘Problem Solver.'” NPR, June 14, 2007.

[8] Ellen Sorokin, “Cardinal Urges Trust in God for Dark Days.” Washington Times, September 17, 2001; William Toti, interview by Mike McDaniel.

[9] Vern Clark, “Meeting the Homeland Defense Challenge”; “Regent Remembers 9/11.”

[10] Vern Clark, “Meeting the Homeland Defense Challenge.”

[11] Cheryl Pellerin, “Mullen: World Changed Forever as Jet Hit Pentagon.” American Forces Press Service, September 9, 2011; “Remembering September 11.” Military Money Matters, September 10, 2011.